The Ring Theory of what (not) to say

/photo by Erin Purcell

When Susan had breast cancer, we heard a lot of lame remarks, but our favorite came from one of Susan's colleagues. She wanted, she needed, to visit Susan after the surgery, but Susan didn't feel like having visitors, and she said so. Her colleague's response?

"This isn't just about you."

"It's not?" Susan wondered. "My breast cancer is not about me? It's about you?"

The same theme came up again when our friend Katie had a brain aneurysm. She was in intensive care for a long time and finally got out and into a step-down unit. She was no longer covered with tubes and lines and monitors, but she was still in rough shape. A friend came and saw her and then stepped into the hall with Katie's husband, Pat.

"I wasn't prepared for this," she told him. "I don't know if I can handle it."

This woman loves Katie, and she said what she did because the sight of Katie in this condition moved her so deeply. But it was the wrong thing to say. And it was wrong in the same way Susan's colleague's remark was wrong.

How Not To Say The Wrong Thing, by Susan Silk and Barry Goldman, was originally published in the LA Times in 2013. There is a right way, it purports, to show up in the company of people in the middle of crisis, trauma, and loss. Conversely, there is a wrong way.

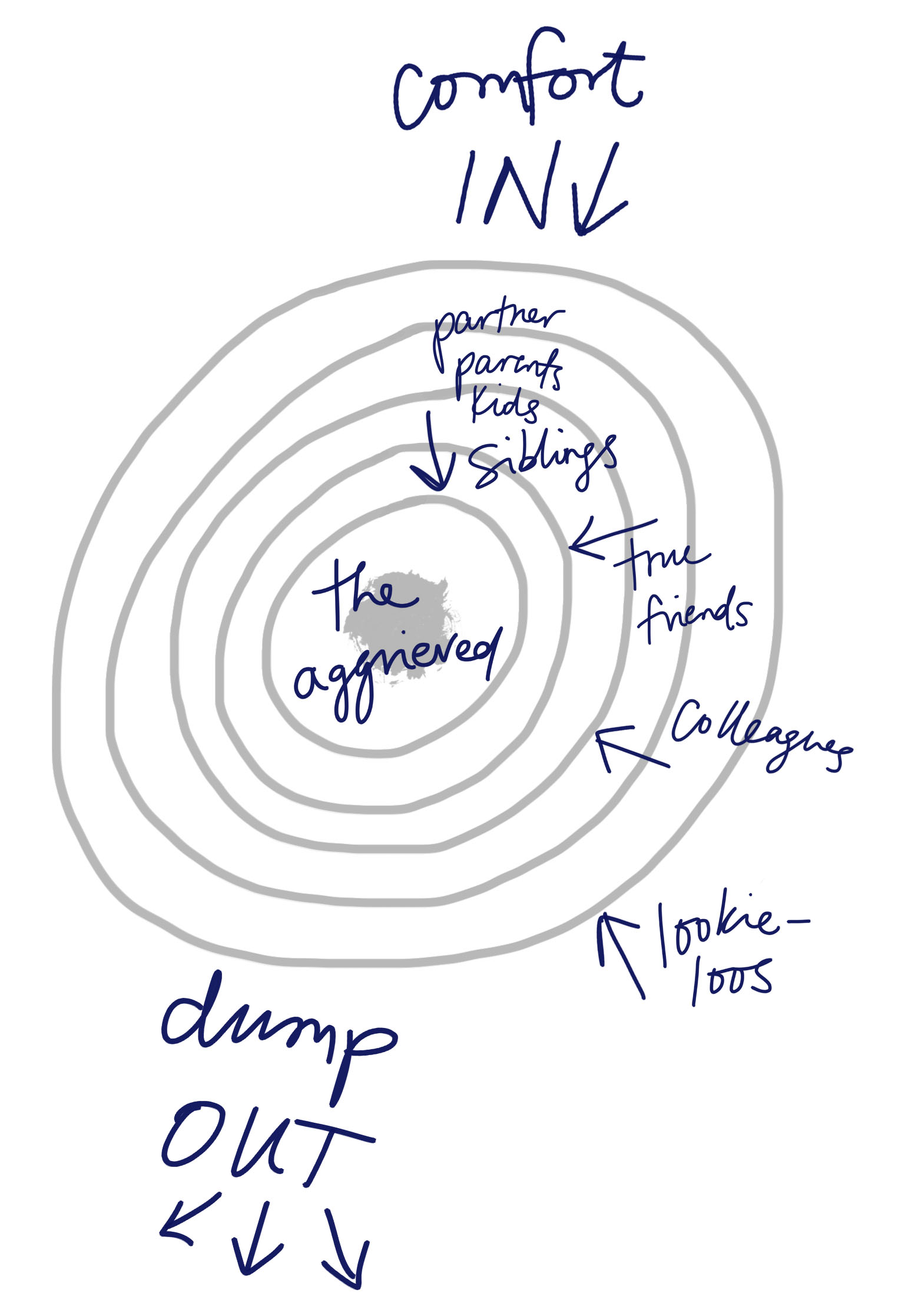

As a bereaved parent, you've suffered the lack of it, and you've noticed a softness in its presence. The Ring Theory, as Silk and Goldman called it, is like this. Your baby died, perhaps inside your belly or shortly thereafter. You're in the middle: the aggrieved. You are suffering an agonizing degree of pain and confusion. Immediately in your periphery is the father of the baby—your partner in love, parenthood, and loss. Then your parents, his parents, any other children you have. All of you a swirling mess of pain and confusion. Together, you form the dot and its innermost blast radius.

Everyone else in your life—close friends, extended family, distant acquaintances, and colleagues—exists in varying degrees of closeness to your pain. And some not at all, like the lookie-loos. The passerby, the town gossips who share the news in a throw-salt-over-your-shoulder way in hushed whispers. The high-school people that you wonder why you're connected to on Facebook.

Depending on where someone is in your periphery—close or distant—the Ring Theory dictates that comfort should flow in from one ring to the next, with those in the verymost centre ring protected from random comments, panic, nightmare fetishization, and uphelpful advice. Venting or teeth-gnashing should flow out from one ring to the next. Never the opposite.

This is harmony in suffering, Silk and Goldman might say. This is the Kvetching Order.

Illustration based on 'The Ring Theory' by Wes Bausmith / LA Times

"Here are the rules," say Silk and Goldman. "The person in the center ring can say anything she wants to anyone, anywhere. She can complain and whine and moan and curse the heavens and say, Life is unfair and Why me? That's the one payoff for being in the center ring.

Everyone else can say those things too, but only to people in larger rings.

When you are talking to a person in a ring smaller than yours, someone closer to the center of the crisis, your only goal is to help. Listening is better than talking. But if you're going to open your mouth, ask yourself if what you are about to say is likely to provide comfort and support. If it isn't, don't say it. Don't, for example, give advice. People who are suffering from trauma don't need advice. They need comfort and support. So say, I'm sorry or This must really be hard for you or Can I bring you a pot roast? Don't say, You should hear what happened to me or Here's what I would do if I were you. And don't say, This is really bringing me down.

If you want to scream or cry or complain—if you want to tell someone how shocked you are or how icky you feel, or whine about how it reminds you of all the terrible things that have happened to you lately—that's fine. It's a perfectly normal response. Just do it to someone in a bigger ring.

Comfort IN, dump OUT."

+++

In the NICU with two babies—one of whom would die—a distant somebody came to me with a gift.

"This is for you," she said. I opened it. It was a blank journal. She went on to explain.

"Because you're not going to want to talk about this with anyone, or write about it.... in public." she visibly shuddered. "So here's a private place where you can put your... feelings. So that nobody else will see it. So that you won't be, you know. Inappropriate. Or make anyone uncomfortable."

She smiled helpfully.

+++

The supermarket, by the dairy case. Yogurt in my hands.

"OH MY GOD I HEARD WHAT HAPPENED, OH MY GOD." trilled the acquaintance from university. Her eyes were oddly bright, almost excited. She spoke breathlessly in all-caps upspeak. "THAT'S SO AWFUL. I KNOW EXACTLY HOW YOU FEEL. MY DOG DIED LAST YEAR."

+++

"You know whats-her-name? Down the street. Her baby died and she doesn't even remember. She never talks about it. She doesn't even remember the day it happened. She couldn't even tell you which day it was. That's how you should be. She's a coper. Not a non-coper. She's not like you. She's over it."

She was like a mother to me. Now, she is not.

+++

The Ring Theory: I'm thinking a face tattoo might work. A bit extreme, maybe. But I want more people to know this, to stop and think: Am I helping, or hindering? Am I making this person's suffering about me? Am I talking, or listening? How can I be of support?

People say There is no right or wrong way to grieve and that's true. The aggrieved grieve as they must, a hundred different ways, as is their emotional autonomy. But there sure as hell is a wrong way to be around grieving people. I've seen it. I've witnessed it. Have you?

I'd love to know: how does the Ring Theory map to your experience of family members, friends, and lookie-loos after the loss of your child? Do you remember moments when someone followed the Ring Theory and was gentle and compassionate with you? Or the reverse?