Everyone has two memories. The one you can tell and the one that is stuck to the underside of that, the dark, tarry smear of what happened.

-- from Amy Bloom, "Away"

I've been chewing on this quote for months now, and I suppose it's time I do something with it.

The line comes from Amy Bloom's novel Away, wherein the protagonist loses her family in a Pogrom and flees to America. And then finds out that her daughter, who she sent out of the homicidal rage to the chicken coop, may (may, maybe, could be? Is it possible? Is she crazy to believe?) be alive. And the book proceeds to outline her physical and emotional journey to discover this truth. It's a beautifully written book, and contains many sentences which were so hard-hitting in their gorgeousness, that I reread them multiple times. And many, like this one, stuck with me.

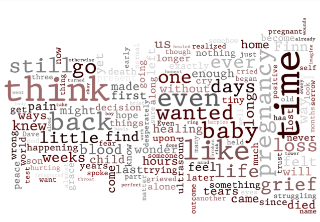

It has come to my personal attention that, uh, (tries to remember what day it is; uses fingers to count) 17 months (!) after the fact, that I'm still "in the closet" to many people in my life (read: nearly the entirety of kids' parents in Bella's class, save for one who's shut like a clam due to that doctor/patient thing), and others (read neighbors) simply know the bare bones: my baby died when she was less than a week old. So I'm now, finally, hallelujah, to the point where I'm totally ok talking about it, and hell, kinda want to talk about it, and I'm faced with what to say. So I got to thinking about the clean, tidy anesthetized version, scrubbed up twice with disinfectant and anti-bacterial, free of pet hair. (OK, maybe not entirely free of pet hair, picks something off my keyboard and something else off my coffee mug.) And the messy, nasty, gutwrenching, terrifying underbelly. There is the story I tell in public, and not even that often, which often simply gets condensed to, "I had a baby, she died when she was six days old." Then there's the underside, the "smear," that gets told here and in therapy, the story my husband knows. The story that gets replayed in my head, and in my nightmares. The two memories, and why I withhold what I do, and why I tell what I do.

For starts, I don't even know where to insert this information into a conversation. No fellow pre-school parent, for example, has ever asked me how many children I have. Or if I plan on having more. Or anything. Which in no small measure, I'm grateful for. But I'm now worried that when the opening comes, it will be like a bomb dropping and leaving a wasted plain. There is, after all, the polite thang. I'm assuming, having long-ago thrown out my Miss Manners handbook on neonatal loss, that it's probably not polite to discuss death of infants at all. I think it scares people. Hence my "in the closet"-ness, and not wearing my "My Baby Died" t-shirt when I pick Bella up. Really, the whole story's a smear -- so why go there?

I'd love to tell you I'm as brash in real life as I am here, but I'm not. Frankly, I don't give two farts about other people's scare-factor after what I've been through, but apparently I do a bit. I don't go there, I don't even give them the nice memory.

Should I broach the subject, there's the why-part, which is really none of their business -- my genetics or infectious self. Inevitably when I tell someone, the next thing out of their mouth is, "Oh my god, what happened?" and I'm left wondering how to elaborate in a way that tells them something, but perhaps not too much, and does so quickly. And I do this, knowing full well that they probably really don't give a shit, and THEY asked me to be polite, and they're praying I don't go into deatil. "She was born with a host of irreparable, fatal problems."

But depending on whom I'm speaking with, part of me wants to start elaborating. To let them know what a shock this was, and that I was not some head-in-the-sand, completely naive late 30-something mother, who smoked or did drugs or drank myself silly for nine months. "I had a clean amnio, we went to term -- in fact, a week late." Am I negating blame? Letting them know how horrific the bombshell was? Warning them that the universe can be horrifically unkind when you least expect it?

And I hesitate to get into the genetic discussion with most people, even though I know they're wondering (I can practically hear it) if we're going to have another baby. I don't want to tell them the odds, because in the event I do become pregnant, I don't want them thinking I'm crazy, or knowing that we've used a gamete donor. Strangely, some people I'd like to shield from this information are in my own family. I don't want them knowing the odds, anticipating, worrying, getting emotionally invested; nor do I want them rejecting, replacing, or writing off. But, honestly? Sometimes I hear myself slipping into the odds, and the scary knowledge that there's "no way to know prenatally." Am I telling them how pissed I am about my chances and choices? Preparing them for failure in case there is another? Trying to scare them too, informing them that ultrasounds are merely gross generalizations that occasionally can predict gender and obvious visible problems, but occasionally fail to discern numerous, mortal conditions?

The two memories.

I had a baby, she died when she was six days old. She was born with a host of irreparable, fatal problems. (I had a clean amnio, we went to term -- in fact, a week late. I have up to a 1:4 chance of this happening again, with no way to know prenatally.)

And the underside of sobbing, anger, despair. The memories of hospitals, tubes, needles, seizures. The discussions about comfort levels, and removal from life support. The knowledge of funeral homes, cremation, and explaining death of a sibling to a toddler. The ongoing aftermath of grief and all of its gross, infectious ooze: sleeplessness, bewilderment, weight I can't lose, short-term memory loss, jealousy, anger, loneliness. All of it ugly. Except for her, of course. She was beautiful, and sadly, not meant for polite conversation.

************************

A couple months ago Mr. ABF came home from a social day of community service with the news that neighbors of ours are "splitting up." It was news that took my breath away -- two people I adore, two people who've been together for what seems an eternity, two people who are part of the backbone of my very lovely comfortable community. And the very next thought, after my heartbreak for them, was the heartbreak for us, how it would impact the neighborhood. They would no longer host or attend functions; their house would sell; their dog, who my daughter insisted on dressing up like on Halloween, would no longer walk by my house. And the NEXT thought was jeebus, this must be how everyone thought about us: heartbreak for them, a cloud over the fun-loving community.

These are people who will now be where I am, with the big elephant in the room, no one knowing exactly what to say, including myself. These people, when pressed, will assuredly also have their two memories -- the one they tell us ("It's nobody's fault"), and the one that careens inside of their heads. They were so gracious when Maddy died, showing up in person at our door, with hugs and tears and an explanation that they really didn't know what to do, so they brought chocolate. Which made all the sense in the world to me. They were people who nudged me out of my shell to say thank you, and people who followed up with me, months after everyone else assumed I was ok, and asked how I was doing -- for real. These are people with whom I shared the honest answer: Awful, but functioning. And so now I feel the need to reach out to them, to let them know I also have no idea what to say or what to bring to the table (Chocolate? Vodka?) but that I'll be there, that I understand the elephant in the room, the uncomfortable realization that you're no longer who the neighborhood thought you were, that you, too, have two memories. I'm not asking to be let in on the underside, I'm not even sure I want to hear it. But I'm willing to bet they'll be grateful that I understand it exists.

Are you "out?" To everyone or a select few? And which -- or how much of your -- story do you tell?