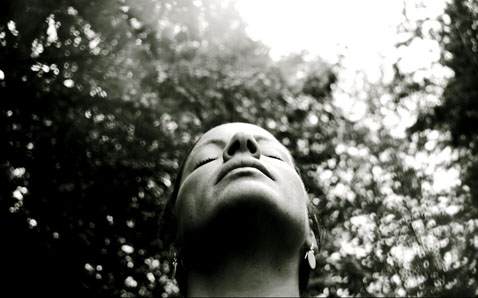

Change

/Every day I make an effort to have a nice time out there in the World. I'm not aiming for the stars, not trying to seize every single moment with fervor and gusto, I'm just gunning for good. Good is enough if you can do it on a daily basis.

I sleep later now, every day. I need an hour or so of semi-wakefulness to gear up and get ready for the chill and sunlight and this relentless, active life. I guess I still can't believe, every morning, that this is the Universe I live in.

I take a shower and I love it. As hot as I can stand it. Sometimes I reflect on how lucky I am to even have a hot shower that I can stand in as long as I like. Sometimes when it looks like a tough one in my heart or my head, I stand there a little longer. I shouldn't because of the coming Water Wars, but sometimes I can't help it.

Guilt is gone. I've banished it. I do what I need to get by and I don't worry about perfection. Except in the coffee I roast. And in the driving. They both need to be perfect but for completely different reasons. Coffee because it feels good to do it right and it's my job, driving because anything less is disaster. I am not down with any more disasters.

The day Silas was born was supposed to be the best day of my life and instead it was by far the biggest disaster I have ever experienced. Nothing like that should ever happen again. But obviously, since we're all here together, Should is a word we all know doesn't mean a damn thing.

So Should is out now, too. Expectations are a fool's game, and I choose not to play anymore. I declare that as if it is something that can be de-selected. Mostly I try to do exactly what is right in front of me and I avoid worrying about what I think should happen next. Maybe it is the not-thinking that keeps me up at night.

3am has become my thinking hour. I know it is going to be 3:11am when I open my eyes. For a while that brief, nightly insomnia upset me, but now I look at it as a special time, just for me. Lu asleep next to me. The cat is tucked tight between us, not even purring anymore.

Usually it's a song that wakes me up. Whatever I happened to enjoy the most that day is usually the one that's still running through my brain. The same refrain, whatever it is. The song-worm, it infects me. I don't even think about who Should be waking me.

If you break these moth's wing feelings, powdery dust on your fingers or undecided undefined undeterred yet undermind and then it's the steady, static hum of my soul trying to reconcile another day without my son.

It doesn't stop, I'm sorry to say. Not so far. Not 2 years after he was conceived. Not a day goes by that somehow isn't all about him.

The ultimate reason for that is because in a way, I have become him. Silas doesn't get to do this Earth so I've got to do each day for him, too. My everyday experience has been utterly transformed, and I do not at all feel like the person I was before Silas was here. Two years since we started this journey and our lives look exactly the same, but everything has changed, inside and out. And like Julia said, it is still happening.

I live my life the way I do as an expression of how my parents raised me, of how I have come to know the World, of how Lu's love and presence have become intertwined with mine. Today is our 5 year wedding anniversary and despite the sadness of these past years it still always feels right that we are together.

Living extra for Silas--any way I can think of--feels right, too.

His brief life has transformed me in ways I am only beginning to understand. I suppose all parents go through this, but it is especially difficult for people like us because we can never hug them and thank them for everything they help us become.

All I can do is hold on to every day, every little treat and happiness. I do what's right in front of me and watch and listen for the beauty that appears. I keep going forward for Silas, for myself, for Lu, and for whatever it is that happens next. I know what that Should be, but I can't worry about that anymore. I can only face what Is and somehow deal with everything that Isn't.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

How have you changed? Do you have expectations of how things should turn out? Do you get the ear-worm of music? What are your refrains? Do you manage to have nice days, despite your loss and sadness?