Ghostbelly: a conversation, part II

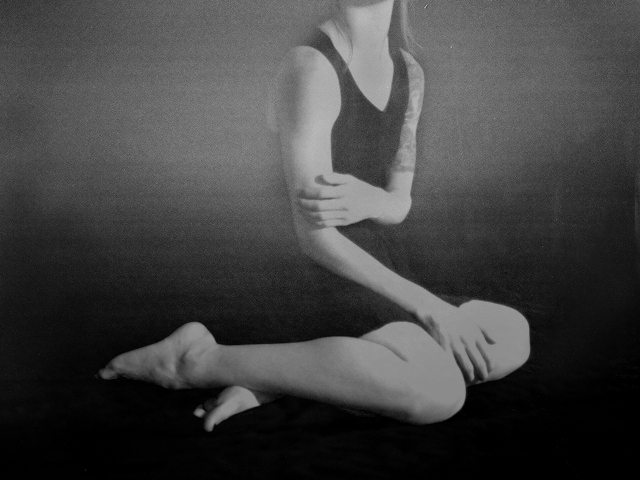

/photo by Erin Purcell

Following is Part II of my conversation with author Elizabeth Heineman about her memoir Ghostbelly. Part I of the conversation is here.

Reading Ghostbelly I was struck by how certain you seemed to be of everything you did—bringing home Thor's body, giving him experiences. After Joseph was stillborn, I had no idea what I wanted. For months. How in the world did you know what you wanted? Would you call it "intuition"?

That’s one of the big mysteries, even to me. How did I know so clearly what I needed to do—and at such a critical early moment? One of the things I hear most frequently from bereaved parents is that they wished they’d spent more time with their child’s body, but they were so stunned they just let the hospital or funeral director take over. By the time they realized they needed something different, it was too late. How did I know what I needed before I’d had a chance to think things through?

Maybe that was the key: I had no time to think, no time to over-intellectualize or get tangled up in the pros and cons of various options. Maybe “intuition” is exactly the right word. In any case, I was incredibly lucky that my intellectualizing brain shut up and my intuitive brain took over. I didn’t do it on my own. If my funeral director hadn’t let me know that taking Thor home was an option, it wouldn’t have occurred to me to ask. But once he put that option on the table, I didn’t lose a second mulling over the question of whether I should do it or not. I knew immediately that it was the right thing to do.

You have such a certainty that Thor's body was Thor. Yet for me, Joseph's stillborn body was the absence of Joseph. We held him hesitantly and looked at him (but didn't unwrap the blanket) and thought, "This is not our baby. This is just his body. Our baby is already gone."

Thor died unexpectedly during birth. But Joseph died two days before he was born, at 35 weeks. I've been thinking a lot about that difference in our stories. You didn't know going into labor that he was going to die. I knew I was giving birth to a dead baby. It's almost like you had this momentum of life going, expectations of bringing your baby home, that helped you shape the next few weeks with Thor. But for me, everything stopped the moment we found out Joseph had died. Everything went dark, like sleepwalking underwater.

Do you think there's anything to this… that maybe the timing of our babyloss (and I'm speaking generally now, not just about you and me) could affect the trajectory of our actions, our reactions, our shock?

I wonder whether this is why you felt from the beginning that this body in your arms wasn’t Joseph, while I somehow felt that the body I was holding was Thor. You knew ahead of time that Joseph was dead; you still had to deliver the body, but you’d already started to come to terms with the fact that he was gone. I went into labor, delivered a baby, and then discovered he was dead. But this was the baby I had.

This was my initial impulse: to get to know my baby. We didn’t even know his biological sex till he was born. So we discovered he was a boy. We discovered that he had thin dark hair, and that he was big. We discovered that he was dead. We were discovering all those things at the same time, and we wanted to get to know him, with whatever characteristics he had.

One of my favorite parts in Ghostbelly was the funeral home director, Mike, and what you call his "complete lack of orthodoxy." We don't typically think of funeral directors as being genuinely comforting or helpful, but Mike was really there for you.

Yes, Mike! Everyone who reads the book falls in love with Mike. In a lot of ways, he really is the hero of the story. He’s the one who let me know that I could visit Thor in the funeral home and even take him home with me. But his personality was just as important as the fact that he passed this information on to me. He was so unorthodox, so allergic to cliché; he even managed to be funny. About a dead baby. It was a way of integrating grief into real life.

Reading about Mike made me think of a sort of unorthodox encounter I had. Six months after Joseph died, I went to my 10-year college reunion. Standing in line to get pizza at our class dinner, I was talking to this guy I'd vaguely known through a friend. He always struck me as this brilliant, crazy egomaniac. He looked at my necklace and asked, "Who's Joseph?" When I told him Joseph was my baby who died, he said, "Fuck! Man, that sucks!" It was such a different reaction than the doe-eyed looks and calm, sweet words of sympathy I'd gotten from everyone else in my life. And I thought, "Yeah! Fuck! Fuck this! This does suck!" It was the exact right reaction, and one of the most memorable moments from that whole weekend. I wonder, are there any other people, besides Mike, that were unexpectedly there for you, or who said something unexpected to you that ended up being just the right thing to say?

My other extraordinary experience of getting-past-cliché didn’t make it into the book. A friend who knew I was writing about my experience put me in touch with an extraordinary playwright, Jen Silverman. I think Jen was initially a little skeptical—she wasn’t interested in writing a conventional tear-jerker—but then she learned I’d brought Thor home, and that story tapped into her fascination with the bonds between the living and the dead. After a lot of conversations between the two of us, Jen wrote a play, “Still,” that moves in the realm of the fantastical. It involves a middle-aged grieving mother (an entymologist!), her midwife (who’s considering a career change), a dominatrix (pregnant with a baby she doesn’t want), and—walking around the stage, chatting up the audience—the baby (who is befriended by the dominatrix but is really searching for his mother). The play is incredible—it’s won a couple of major drama awards in the meantime. For me, though, the process of collaboration created a space for talking about death in a way that felt much more honest than ritualized phrases and hushed voices.

Wow. That’s pretty amazing, about the play. I’m honestly a little jealous you were able to participate in that collaboration. Writing is such a solitary venture. Grief is solitary, too, even if we are surrounded by supportive loved ones. It’s rare to have a space to talk about death, like you said. I think that’s one of the special things about Glow. Are you still writing about Thor, about grief? Or was this book everything you needed to say?

It’s hard for me to contemplate writing a new essay about grief. I don’t feel the same urgency about writing about Thor that I once did. And I really did say what I wanted to say at the time.

But that doesn’t mean the story you read is the final word, because my relationship to Thor and my thinking about that time continue to evolve. Many people say you shouldn’t write a memoir until a lot of time has passed—say, fifteen or twenty years—so you have some distance from the events and from the person you were at the time. But what I wanted to convey was the immediacy of grief, and if I’d waited, I would have lost that.

Thank you so much for sharing your story with us, for writing your book, and for being willing to engage in this conversation here at Glow. Usually at the end of a piece on Glow, we invite the readers to respond, and Lisa has generously agreed to continue the conversation with our readers here in our comments.

If you'd like to know more about Ghostbelly, it's been added to our bookshelf. You can also visit The Feminist Press website or the book's Facebook page.

How has writing helped you in your grief journey? How has reading others' stories and memoirs helped? Continue the conversation with author Elizabeth Heineman--questions, reflections, reactions—here in the comments section.