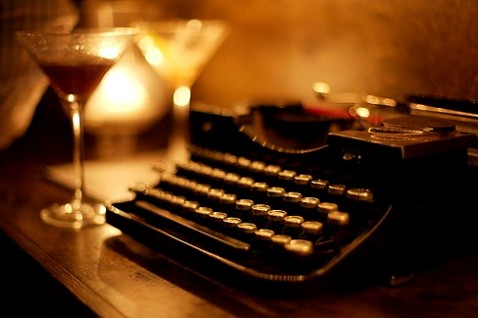

photo by ldandersen.

I pull the darkness up to my chin, and curl my knees up under her. The alcohol is a nice way to turn off the refrain. My eyes force themselves closed in spite of the insomnia that has plagued me all my life. I am a lump of unconscious. No dreams. No waking. No dead daughter. Just the mind switched off.

In my most raw moments, in the early days after Lucy died, I made some very lucid decisions. One was to not drink for a few weeks. I thought booze would tear me open, dump my necrotic organs onto the floor in front of me. Liquor will only make me cry more, I reckoned. It might even make me suicidal. Maybe I will scare my daughter when I am drunk and full of grief, guilt and self-hatred. Maybe there was a demon in the bottle which would possess me and make me more sad than I could possibly imagine. I would be swallowed whole by bourbon, that is what I thought.

The alcohol would not have made it to my brain, I suspect now. It would have kept working on the large, pulsating hole right through the center of my abdomen. It would have been covering it over and over, dulling it slightly, but never leaving it alone. And I probably wouldn't have noticed the drunk. Still, there was a healthy fear of the unknown--grief drinking seemed dangerous to me.

I started drinking again because I figured it couldn't hurt anymore. I was nigh-suicidal, my organs were on the floor anyway, and it ached more than I could imagine. The wine slipped over me, like an old comfortable lover who knew just where to kiss me every time. I felt normal, like a normal person, not a grieving mother. Just a person enjoying a glass or five of wine with some dinner. Drinking has always been a kind companion for me, not something that drove me into a depression or into psychosis, rather like an old friend, a confessor, listening to my self-pitying ramblings over a glass. We would laugh, sometimes cry. I felt better just having the booze near me.

A glass turned into a bottle. And when it took over my nights, I stopped, because I wanted to get pregnant. And then I was pregnant and absolutely did not drink. But every day I thought, "This pregnancy might be fucking manageable if I could have a bourbon." I would mention nearly every time I was at my midwife. "I could really use a bourbon, Pam." And she would laugh, and I would look at her. "No, I'm serious."

A pregnant dry drunk may be the curse Dionysus unleashes upon humanity. I was a miserable, unpleasant person to be around or know. I embodied anxiety and misplaced anger. I was not the pregnant person that people would approach, hands outstretched headed towards my expanding belly, with the question, "Is this your first?" No, I would stare at people with a thousand dagger stare, "Touch me and I cut you, bitch."

Then Thomas Harry was born. Whew, glad I was done with all that nastiness. I was out of the woods. Everything was happy. Here is a new cute, adorable baby who doesn't cry very much and sleeps great. My life felt pretty complete. My grief, while not absent, felt under control.

"Let's toast," I said. "Let's toast to our good fortune."

I felt like my grief was under control. I felt like my drinking was in my control. And now, I am trying to get sober.

+++

People drink for many reasons. I drank because my kid died and I deserved a fucking drink. I drank because I couldn't sleep. I drank because I like the taste of wine and bourbon and beer and vodka and any other drink with a proof level. I drank because I was sad. I drank because I was happy. I realized, not that long ago, that I really only drink for one reason--because I am an alcoholic.

Drinking problems are usually measured in quantities and horror stories. I know that there is a blackout-drunk-lose-everything bottom for a lot of people.

I am not that person.

I have children. I have a husband I love. I have a life I love. I have lost nothing material. What I lost was any respect I had for myself. I lost peace. I lost contentedness. I lost feeling well. I lost restfulness. I lost hope. I raised my bottom up to a place that was low enough for me. As a mother, I often relegated those things to some day. Some day, I will sleep. Some day, I will take care of my drinking. Some day, I will be happy.

My husband didn't even realize that I drank at night after the kids went to sleep. I have never driven drunk. I have never missed a bill, or woken up to a drink. My kids have never seen me drunk. When I drink, I write.

I shut the door of my office and fall into a world of 75 words per minute. I edit. I paint. I create an alternate reality where Grief and Bourbon are my muses. But I was still miserable. After waking in the morning, cotton mouth, cloudy with a dull headache, I vowed not to drink that night. By 8 pm, I was talking myself into one glass of wine. Just one glass. After one glass of wine, or one bourbon, or one beer, all bets were off. My resolve was gone. I maybe had two more, or four more, or maybe more. I called a hotline one day.

"I don't know if I have a problem."

"Did you answer the questions on our website?"

"Yes. I think I got an A."

"Ha, yes, I got an A too."

"I used to drink more when I was single. I haven't even been drinking for more than three months. I am not anywhere close to a rock bottom," I tell the woman on the phone.

"You are at enough of a bottom to think you have a problem. And besides, bottoms always have trap doors," she says to me.

"But I don't drink very much on the average, and I am very good at quitting. I am just not any good at staying sober."

"But staying sober is the important part to you, right?"

"Yeah."

"How do you feel when you drink?"

"Ashamed. Pathetic. Weak."

"Pay attention to that."

+++

It has been a seventy days without a drink. I am happier than I have been in years. With Lucy in my belly, I remember saying that I wouldn't drink after she was born. I didn't realize I was a drunk, then, but my brain made some feeble connection that when I drank, I felt bad about myself. Then she died. And stopping drinking was the last thing I thought would help me.

Someone told me recently that Lucy's gift to our family was my sobriety and that I would never have gotten sober if she had lived. That is true. Drinking after Lucy's death immediately was not fun. It was like medication to keep me normal. Or rather the social lubricant I needed to be alone with me.

I thought I was smarter than being an alcoholic. I thought I could outsmart my family's legacy of booze and drunks. What I learned is that the arrogance of thinking that way prevented me from getting healthy. My arrogance prevented me from calling people at my most desperate hour to say, "I need a friend to talk to. I need a friend because my daughter died. I need a friend because I think I am drinking too much." It seemed easier to get drunk, and in fact, it was easier to get drunk, but it wasn't healthier or smarter.

Alcoholism is a progressive, fatal disease. When I began drinking, after my one year old son was born, I didn't immediately drink to drunk. In fact, the last few months of my active drinking, I can't remember feeling drunk ever, even when I would stare at the evidence of having drunk a bottle of wine. I would stare at the empty bottles of liquor clogging my recycling bin, and think, "Next week, this will be filled with Pellegrino bottles. Next week." But it never was. Drinking felt like a choice. It felt like I was handling the bourbon, except that when I tried to quit, I would drink again. I was sober for two days, I would reward myself with twice as much Maker's Mark on the rocks, and drink myself tired again. I didn't know, until I began reading about alcoholism, that this is a pattern for alcoholism.

Despite the fact that I am strong-willed enough to make outrageous goals and challenges (riding one hundred mile bike rides, writing a novel in a month, or posting a piece of art every day on a website) and meet them, I thought drinking was a weakness of mine, and that I was simply a weak-willed person. Looking at alcoholism as a disease has helped me be more compassionate. The moral defect here is simply not seeking help earlier. Some people describe alcoholism as an allergy to alcohol, because alcohol in an alcoholic creates a series of undeniable reactions--I can't say no to another drink once I have had one. If you ate a strawberry and your throat closed, you would not call yourself weak for your bodily reaction. What I have control over is whether or not I eat the strawberry at all.

I used to think that for me quitting drinking was like someone telling me to lose weight by cutting off my left leg. I mean, sure I would lose weight without the leg, but everything would else would be near impossible. I always wanted to be spiritually/mentally/physically well AND have drinking. That is simply not possible for me. And these days of sobriety, I also had to seriously think about why I would look at drinking as my left leg.

Right now, I feel like all the skin has been peeled from my body. I feel as raw as the early days after Lucy's death. And I am scared as hell. It's not that I can't do this, it's that I can. And now I have to feel the weight of Lucy's death and of my losses without numbing it with alcohol. I am wrestling with losing my medication, my best friend, my confidante, my muse, my partner, my inspiration, my wubby, my safety net, my identity, and my number one enemy. But one thing is absolutely clear, the shame of drinking, the self-abuse I engaged in over every drop of alcohol I took in, that feels lifted. I feel a freedom and a lightness in this place of absolute vulnerability, and that is addictive too.

Due to the nature of this post, please feel free to utilize posting anonymously. What is your relationship with drinking like? Have you sought to numb your grief with alcohol or drugs? Have your habits gotten worse or better since your loss?